The World Health Organization on Wednesday declared mpox a global public health emergency for the second time in two years, following an outbreak of the viral infection in the Democratic Republic of Congo that has spread to neighboring countries in Africa.

A “public health emergency of international concern,” or PHEIC, is the WHO’s highest level of alert, and it can accelerate research, funding and international public health measures and co-operation to contain the disease.

Earlier this week, Africa’s top public health body similarly declared mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, an emergency after warning that the viral infection was spreading at an alarming rate.

More than 17,000 suspected mpox cases and 517 deaths have been reported on the African continent so far this year, a 160% increase compared to the same period last year, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. Cases have been reported in 13 countries.

Mpox has two distinct viral clades, I and II. Both versions can spread through close contact with an infected person or via direct contact with infected animals or contaminated materials.

The outbreak in Congo began with the spread of clade I, a strain that is endemic in central Africa and known to be more transmissible. Clade I can also cause more severe infections; previous outbreaks have killed up to 10% of people who got sick.

A new version of that strain, clade Ib, is now spreading and appears to be more easily transmissible through routine close contact, including sexual contact. It has spread from Congo to neighboring countries, including Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda, triggering the action from the WHO.

“It’s clear that a coordinated international response is essential to stop these outbreaks and save lives,” said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

A strain of clade II, meanwhile, was responsible for the global spread of mpox in 2022, which prompted the WHO to declare a public health emergency. Infections from that clade are far milder than those from clade I — more than 99.9% of people survive, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But it’s still capable of causing severe illness, particularly in people with weakened immune systems.

The version that spread in 2022 — largely through sexual contact among men who have sex with men — was known as clade IIb.

The WHO ended that emergency declaration 10 months later. In the U.S., mpox cases have declined considerably since their peak in 2022. Average daily cases fell to zero in the week ending Aug. 1.

However, given the virus’ spread in the DRC and its bordering countries, the CDC asked doctors last week to be on alert for mpox among people with characteristic symptoms who have recently spent time in the area. No cases of clade I have been reported outside central and eastern Africa, the agency said, but it warned about the risk of further transmission.

The CDC has also issued an advisory for people traveling to the DRC and its neighboring countries. According to the agency, these people should practice enhanced precautions and seek immediate medical care if they develop a skin rash.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said Wednesday that the country is well prepared to detect and manage any clade I cases that might arise, since health officials monitor for mpox through clinical testing and wastewater surveillance.

If a clade I cases were detected, “we expect it would cause lower morbidity and mortality in the United States than in the DRC,” HHS said in a press release.

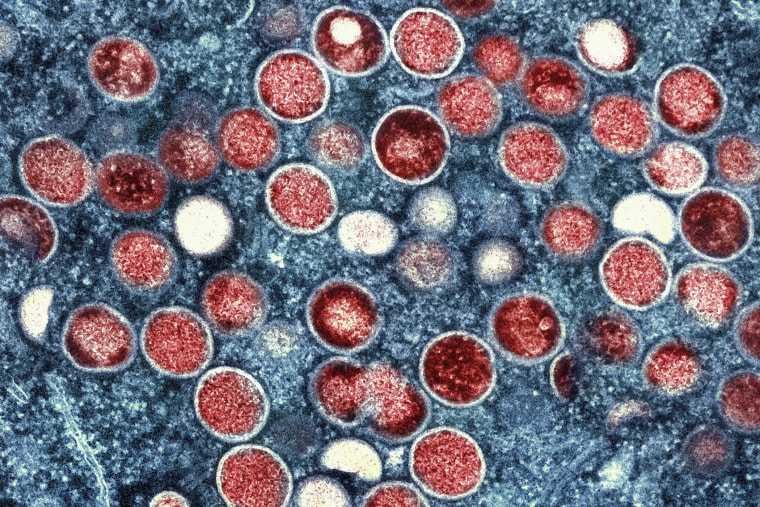

Mpox usually starts with a rash that can look similar to chickenpox, syphilis or herpes. The rash typically progresses to small bumps on the skin, then to blisters that fill with whitish fluid. The illness is often accompanied by fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, low energy and swollen lymph nodes.

A vaccine for mpox is available in the U.S. but not generally available in the DRC. The U.S. is donating 50,000 doses to address that gap, HHS said.